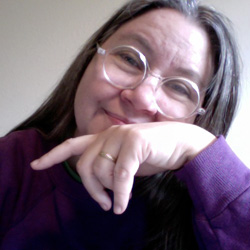

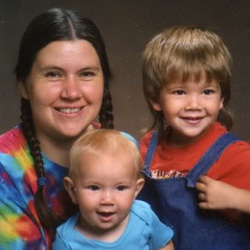

When we heard about unschooling this week on "GMA" (Good Morning America), we weren't sure what it was all about. We wanted to find a mom who had unschooled her kids and felt this was the right decision for her family. That led us to Sandra Dodd, who unschooled her three children -- now aged 18, 21 and 23. They never had one day of "normal school" -- and Dodd has no regrets.

momlogic: Why did you make the decision to unschool your three kids?

Sandra Dodd: It wasn't "a decision" made all at once. We registered to homeschool the first for kindergarten. That was so easy and fun, so we went another year. Each child had a choice to stay home or go to school, and by the time the third one chose home, I had five years of good unschooling experience and it was an easy choice, because our home life was peaceful, busy and interesting.

I knew four homeschooling families for a few years before I considered homeschooling. Two were doing school at home and the other two were unschooling. The unschooling families had great relationships with their children and the kids were more open, honest and communicative. I wanted that.

ml: Can you explain what "unschooling" means to you?

SD: Unschooling is arranging for natural learning to take place. It involves having a rich environment and respecting children's ideas and interests.

ml: What's the difference between unschooling and homeschooling?

SD: Unschooling is homeschooling, but it's not school at home. Not all homeschoolers recreate schools' schedules, lessons and tests. Some families have book reports and other things that have to do with management of large groups. It's as though they've brought the assembly line home for just one child, or a few children.

Some people homeschool because they think schools teach too much and aren't controlling the kids well enough. Some people homeschool because they think schools teach too little and control too much. I don't mind my kids learning things schools fear to teach, or having choices in their lives. Practicing on small things gave them knowledge and experience when they were old enough to practice on larger things. Some families homeschool to limit their children's access and freedom. For us, it's the opposite.

ml: You've said that your only regret about unschooling was giving your son two and a half reading lessons at age 7 -- can you elaborate on that?

SD: I was concerned with the opinion of my in-laws. My son wasn't ready to read. I bribed and pressed, and partway into that third lesson I looked at him and realized I needed to care more about how he felt than what my mother-in-law thought, and the partnership and relationship with my child should be primary. I knew he would learn to read, and he did. His breakthrough "reader" was a Nintendo player's guide, not at all "a beginning reader." First he learned to read maps and charts. Then the words came. Being read to and being surrounded by text didn't hurt, but it was his interest and desire and mental abilities all coming together that made it happen effortlessly.

My other two learned to read differently, but on their own, too. We answered all their questions and helped with words and discussed why English spellings are odd sometimes, but those were conversations and not lessons. Each person, in school or not, figures out how to read in his or her own way.

ml: How do "unschoolers" learn to read and write?

SD: Children want to do what parents are doing. Parents who write for fun, make lists in front of their kids, read and write letters (or at least e-mail) and share that with their children are making it seem important and useful. Parents who don't write at all might have a harder time having children who wanted to do it, but we had no problem at my house. Their early writing was often lists of things they owned or wanted, or the rules to games, or poetry. Sometimes I would transcribe and they would rewrite, but it wasn't an assignment, it was a game, done because they thought it would be fun. And it was fun, because when it stopped being fun they did something else.

ml: You used to be a teacher -- did that factor into your decision to unschool your kids?

SD: The education classes I took were in the early 1970s, at the height of the school-reform movement, at a university where "The Open Classroom" was valued and promoted. I taught in the days that teachers were given a great deal of free rein, in a school where many of the other teachers had known me my whole life. That was good. But school reform didn't take, and things slid back to less creative ways again. I'm sure the experience made it easier for me to have confidence that a rich environment and attentive adults could be enough.

ml: Your kids are now 18, 21 and 23. Can you give us a bit about how they're doing now -- whether they're in college, employed, have their GEDs, are happy?

SD: They're all happy and healthy and involved in various things. No GEDs necessary. The oldest lives in Austin and works for Blizzard Entertainment. For those who don't know what that is, it's a strong and growing international company. They paid for his move, he has good benefits and paid vacations. For those who do know what Blizzard is -- yes, it's a cool job. He's been working for them since he was 20.

The middle child has had three jobs, all of which has lasted over a year. That's pretty good for a 21-year-old. He's a drummer. He's buying a Jeep. Recently he's unemployed, but it's partly our fault. He helped me with a couple of unschooling conferences, and helped his dad after shoulder surgery recently. He's had some housesitting and childcare gigs that paid well. He's undecided about job or college, though he's registered for the community college for summer. Friends keep inviting him on out-of-town trips and it doesn't bother us at all that he's taking advantage of those opportunities.

The youngest is in Quebec for a few months, living with a trilingual unschooling family and helping them with their young daughters. They'll be going to a conference near Montreal in June. I'm going to visit before then, on the way to a different conference at which I'm speaking in New Jersey. Last winter, she spent six weeks in the U.K. with an unschooling family, and before that she was in Oregon with a family she's known for several years. She's getting to see other parts of the world and learn more about family dynamics, which has always interested her. The host families get to know someone who grew up without school, which helps them have confidence that unschooling can work.

ml: Do you have any regrets about unschooling your children?

SD: None. I would do it again in a heartbeat.

ml: What is "radical unschooling"?

SD: Unschooling is learning from the world around. Radical unschooling has to do with seeing that learning is much more than academics, and that learning happens all hours of the day and night, not just "during school hours." It's not radical in a revolutionary way. It's radical in that it is based in the root of the idea of natural learning.

ml: How do you respond to people who say unschooling is irresponsible?

SD: No one who knows our family in person ever says that. When strangers who don't know what they're talking about say it, I offer them a link to my blog or website.

ml: What's your advice to others considering unschooling?

SD: There's not a quick, short answer to that. I help others understand unschooling all the time, every day, and have for fifteen years or more. It's simple but it's not easy, because the parents need to recover from and overcome the deep fears and prejudices that come from years of schooling. A child will recover from school quickly, but it takes longer for the parents. Many have done it, though, and found their lives to be more joyful and light. I advise them to be their child's partner, not his adversary (advice I was given by a La Leche leader in 1986). I tell them to look directly at their child without overlays or filters or labels -- to see who he is, right now, and respond to that. I say if they're worried that they're not doing enough to make life interesting and sparkly, they should do more. Many unschoolers have contributed writings and ideas and images we can refer newer unschoolers to. Information and inspiration are available.

Some people say, "But I have an outside job." Learning doesn't need to happen "during school hours." Even if a parent works 40 hours, there are still a lot of learning-hours left in the week! Where the children stay while the parent is at work doesn't need to be "school." It could be any caregiver. Once a parent gets into the swing of unschooling, she'll see that learning happens all the time.

ml: Do you think public school can squash the love of learning in some kids?

SD: Everyone knows that.

ml: Did your kids have rules like bedtimes, no candy before dinner ... that sort of thing?

SD: We didn't have those rules, but our kids went to bed every night and didn't eat candy before dinner. It seems crazy to people who believe that the only options are rules or chaos, but our children slept when they were sleepy, and ate when they were hungry (or when something smelled really good, or others were eating), and I was pleasantly surprised to learn that they were able to know what their bodies needed. I grew up by the clock, up at 6:30, eat quickly, bus stop, school, wait until lunch, eat, wait until dinner, go to bed. I had no idea that sleep and food could be separated from a schedule like that, but they can be.

ml: Did your children have friends growing up?

SD: We were involved in La Leche League, and we've stayed in the same town, so there are still friends they have now whom they've known since they were babies. They've had friends from karate, hockey, dance, homeschool playgroups, the gaming shop, and met friends of those friends. They made friends playing Pokémon when that was first big. Our house was a hangout, too, with extra tables, board games, video games and room to stay over. Kirby was involved in an animé club for several years, and went to conventions in Denver, and would be sent to run the animé room at local events.

They've also made unschooling friends increasingly over the years, from all over the country -- people they met at unschooling conferences. They've visited in other states, and we've had visitors.

ml: What are some of the unconventional ways that your kids learned outside of the classroom?

SD: Video games and collectible card games. At first I thought "nothing unconventional," but I'm sure many people would think so. We did a lot of singing in the car, sometimes kids' things intended to be educational, and sometimes things that were just funny. All my kids liked '60s music as youngsters and are good singers, so there has been a lot of music-related interaction and research. As early readers, they had lyrics of songs they liked. We've always discussed things and looked things up. We have interesting books and posters and humor and plastic study sheets in the bathroom.

I've always put things out on tables, counters, in bathrooms, just because they were fun and interesting. Kids would find them, pick them up or not, play with them or talk about them. When they stopped being interesting, I'd put them away and bring something else out. I termed that "strewing," and many families have borrowed that concept with great results.

We never "made" our kids get jobs, but they had jobs from age 14 or 15, and learned a great deal from the work and from the coworkers (another source of friends). They learned by volunteering to help people do things, and they were offered jobs because they were willing to help freely, too.

ml: Is unschooling legal?

SD: Homeschooling is legal, and unschooling is a way to homeschool. Each family needs to understand natural learning well enough to make it work in such ways that they can be confident that their kids are learning. Regulations are very different state to state, but there are unschoolers in every state who can advise others on how to fulfill the local requirements. Despite reports to the contrary, unschooling is not "doing nothing." There's a great deal of doing involved!

ml: Can unschoolers go on to become successful adults?

SD: Of course! By the time they're adults they've already been in the world for years. They're not kept home until 18 and then let loose to go wild. Each of my children, in unrelated ways, was offered a job in their mid-teens, by adults who knew them and saw their reliability and intelligence. They've proven themselves to be honest, thoughtful and eager to work and to learn. They always gave two weeks' notice if they were quitting, while kids around them were just leaving jobs without even saying they were gone.

One of their local unschooling friends got a job at a cell-phone call center when he was 16. By the time he was 18, he was a supervisor. One of the newer workers (a high-school graduate) complained when she found he didn't even have a GED, and he outranked her. School had made her false promises about the value of a high-school diploma. He had been working there for over a year, really knew the job, and was reliable. Those things are more important than diplomas.

All of my children have worked in jobs alongside college graduates. Mine did so without college loans to repay, though they might pick up some college debt yet. My husband didn't get his engineering degree until he was nearly 29, and he went through public school and then straight to college. He ran out of steam, tired of school and schooling, by the age of 20. It came back to him, though, once he had some time to recover. My kids won't need to recover from schooling.

ml: Anything else you would like to add?

SD: I expected my children to learn, and they did. What surprised me was their ease at dealing with people of all ages, from younger children to adults. They made eye contact and shook hands from an early age. They're poised and confident.

There were many benefits I hadn't expected, and all were positive. The most difficult part of all is criticism from those who have no idea what they're talking about. Confidence grows, though, as families unschool, and soon the criticism seems less frightening and looks more like jealousy or resentment or fear.

Unschooling isn't a movement to take down schools. It's one of many options. It's not easy, and each family does it at home, in their own way. That alone makes it difficult. It's not like showing up somewhere each day and smiling and letting others make your children's lives interesting.

Part of the resentment and fear involves the fact of having a choice.

Although I loved school in general, I remember when I was unhappy

about something there my mom would say with confidence that I had to

go, there was no choice, that it was the law and my parents would be

in trouble if I didn't go. It's easier when parents can say that.

It makes the parents innocent of their children's unhappiness, or any

harm that comes to them, if the parents had no choice.

When other parents find an option and take it, that shows that there is an

option, and the security of "no choice" is gone.

It's why many

school-at-home families complain about unschoolers, too. They've told

their kids they have to sit at the table and do schoolwork; there's no

choice. When their kids meet unschoolers and say, "But Marty doesn't

have to ..." the parents get mad at the unschoolers for disturbing the

peace. As I was unwilling to sacrifice my children's happiness and

joyful learning to make others feel better about what they're doing,

though, it couldn't be avoided. I certainly was not unschooling to

make anyone unhappy!

The mom-logic site was apologetic too, for having published this: