Piaget's Cognitive Phases (replaced the original page with one from a few years ago)

Learning and Teaching.com's Piaget page, including criticism and updates. That whole site is great gone, so I brought an archived version of the page.

Jean Piaget was a Swiss professor/scientist who studied how knowledge develops—how learning works. His "theory of cognitive development" is studied by aspiring teachers, psychologists and by parents. It's worth having a general idea of what he discovered.

The ages are general. Some children take longer at one stage than others, the same way some get taller sooner, some walk earlier, etc.

"Sensorimotor" stage: birth to two or three (some children longer)

Children need to touch and play and see, and the feedback they need can be of a "getting warm" and "getting cold" nature: looks, encouraging or discouraging tone of voice. Don't expect them to understand anything complicated or to follow directions. One big thing babies learn after a while is "object permanence"–that parents or toys still exist even when they're out of sight. It's peek-a-boo season!

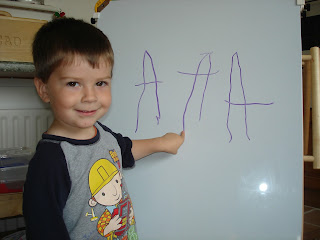

"Preoperational" stage: language use to age 7, more or less.

Ideas begin to form about things that can't be seen. The names of things are sorted out, and differences and similarities are important to them. Speech can get ahead of concepts, though. A child who can talk about time in hours or days or weeks can't really conceptualize it or use it as well as he will later. Parents expect too much too often, of children this young. Try to respect their imaginary friends or their theories of how the world might work. Don't discourage their fantasies.

"Concrete Operations": age 7 to puberty, give or take.

Ideas start to be more realistic and logical. They might want to discuss things longer than the parents like. Parents should tough this stage out. A huge amount of learning is taking place, and the child's internal model of the universe is starting to form up. You can help!

"Formal Operations": puberty into adulthood, but this isn't something everyone comes to. For one reason or another, some people don't develop logically as well or as early as others do. Don't worry about it, though. There won't be a test. And if Howard Gardner is right, then Piaget's set of developmental stages might only work ideally for those with a high logical intelligence.

Parents can make a big difference by helping children work through their thoughts and theories without scoffing or criticizing.

Awareness of this pattern of development can help parents avoid expecting young children to think in ways of which they are incapable, and avoid holding children responsible for "understanding" or "agreeing to" things they can't really comprehend.

Some parents will say, "I explained it and he said he understood." What probably happened was the child heard "blah blah blah blah, okay?" and said "Okay."

There is criticism of Piaget for studying his own children more than having a general sample (and for being a crap dad on top of that, which matters to some people). Take any of these predictive charts as a vague idea, and not 'the rules'—learn from it, think about it, but see your own child as directly as you possibly can.

Many prefer Erickson's stages of psychosocial development. It wouldn't hurt to read both. Erikson's Psychosocial Stages Summary Chart

In a discussion about helping two-year-olds realize and understand this or that about toys being there later, or about sharing and ownership, Pam Sorooshian wrote:

This is also a brain development stage, though. You cannot persuade a kid that things have "permanence" until their brain has developed the ability to grasp the concept. There are some fun little Piagetan experiments you can do with little children that help parents understand that you cannot force a child to understand something that their brain isn't capable of understanding.Joyce's responses to these statements in that same discussion:For example, if your child is under 13 to 15 months old, they probably don't recognize that they are looking at themselves when they look in a mirror. Try this - use some paint or lipstick or something and put a bright red dot on their nose. Have them look in a mirror right before you do it and then right after. When they are younger, they'll notice the red nose and point to the nose in the mirror and laugh. Do this once a month or so - suddenly, one time, they'll reach toward their OWN nose (not the one in the mirror) and indicate that they realize that red nose is on themselves - not just a face in the mirror. It is VERY obvious that a change in the brain has taken place.

The same kind of development happens with object permanence. It is why peek-a-boo is fun for children. There is an age at which things that are out of sight are considered gone and an age where they know that something covered up is still there. As they are developing into the latter stage, they take delight in discovering, over and over, that something can still be there when they can't see it.

-pam

My daughter has now a strong sense of ownership, she is saying more the words “it is mine” or “it’s my turn”. Maybe this is a reflection of me telling her “this toy is not yours” when she grabs the toy from the other child.

More likely it's the next stage of brain development. For some kids the stages—and their new behaviors—come gradually. For some kids it's like a light switches on and suddenly they see the world in a brand new way.If you can get hold of the books Pam mentioned from the Gessell Institute by Louise Bates Ames, they describe what children are going through in each age well. It's a series title Your One Year Old, Your Two Year Old, Your Three Year Old, etc.

Here are links to the Two Year Old and Three Year Old books at Amazon.

You can read the covers and a bit inside of each there.If you're not in America they might be harder to get, though!

[as to whether toddlers need to own things] Not own as in permanently belong to her. Own as in it's hers for now. If she's playing with a toy, she'll be upset if it's snatched away from her. If she's sitting in a chair she'll be upset if someone pushes her out and sits down.

While kids aren't miniature adults, they aren't alien creatures either. She understands the world differently than adults, but her reactions make sense from her understanding. And if you could understand how she sees the world, her reactions would make perfect sense to you too.

She isn't old enough to understand the toy isn't hers. She isn't old enough to understand she'll hurt someone if she seizes possession of something someone else is playing with. From her current understanding of the world it belongs to her and she'll react the same way an adult would if someone took something that belongs to her. That's why distracting them with something else works better at that age than reasoning with them 🙂

Joyce

Stages of Intellectual Development In Children and Teenagers, Child Development InstitutePiaget's Cognitive Phases (replaced the original page with one from a few years ago)

Learning and Teaching.com's Piaget page, including criticism and updates. That whole site is

greatgone, so I brought an archived version of the page.

Photos are Links