Extras with Sandra Dodd

#52 of 50, of The Unschooling Life Podcast

Shauna

April 4, 2015 at 9:07 pm

I just need to say thank you for putting together this beautiful podcast series. They inspire, motivate, and encourage me as a parent and I’ve thoroughly enjoyed and learned from every episode. Some I’ve listened to multiple times. This podcast has helped give me confidence to shift toward an increasingly less structured and more joy-fueled home “schooling” approach, and I am seeing such positive changes in my kids and in my relationships with them as a result. Amy Childs, you and all your interviewees are awesome.

Veronica

April 6, 2015 at 3:55 pm

I love this one so much, everything about it but here are the top 3:

1) Sandra

2) baby steps

3) read a little… try a little… wait a while… watch.

Amy:

Over the past six months, I've had a lot of great conversations with Sandra Dodd, and enjoyed the opportunity to interview her about unschooling.Sandra :Once I'd reached my 50-episode goal, I still had a lot of recordings left with Sandra that I wanted to share. So that's what we have for this episode—all the other things that Sandra said—today, on The Unschooling Life Podcast.

I think it might be true that nobody has volunteered as much of their time, or given as much thought, or made as much of an impact on spreading the ideas of radical unschooling than Sandra Dodd has. And whether that's true or not, I just so happen to like Sandra. My daughter, Nikiah, and I stayed at her house in New Mexico a couple of years ago and we had a really great time. Sandra's funny and smart and generous and articulate and fun.

But Sandra doesn't like it when I talk about her. She doesn't want it to be about her. She wantes it to be about unschooling and how people learn. I know I've made a few mistakes in this regard. For example:

You're getting me in trouble, too.Amy:

What did I do that got you in trouble?Sandra:

You said I was a teacher, you said I was a minister. I'm amused but, you know— but I'm just such a magnet for people to get pissed off, it just stuns me. And it can't be the way I smell, because it happens at a distance. You know, I mean, it's like when some people get bullied because of the way they make eye contact or their posture or something, you know? When I'm in person like, you know, people laugh and it's all light, but somehow at a distance I can make people bristle up.Amy:

Yeah, that's one of the things that I admire about you, is that you're willing to keep doing it, even though so many people lash out at you, just completely irrationally and annoyingly in a way that I would have no patience for. It would just make me cry and hang up on them and never talk to anybody again.Sandra:

When I was in my twenties. It did make me cry.1:47

Do you want me to take the word "minister" out of there? I liked it.Sandra:

I think it's fine.Amy:

We need to be ministered unto we just need a minister who has something worthwhile to say.Amy [to listeners]:

So for the record pretty much time I've ever said anything about Sandra, I did not have her permission, and I might have said it wrong and you should blame me, not Sandra.Sandra:Here's a little clip from later that day. The topic was principles and I was asking why she was refusing to actually say any principles on the podcast. She is really, well… principled about it, you might remember from that episode. She didn't want to be the person who dictated principles to other people. She wanted them to think about it for themselves and find their own principles.

I kind of do want to define it, but I kind of want them to figure it out. And I kind of want to trap people who want to say, "But you didn't tell us what principles are." I was like, "Next! You're out. Send your kids to school."2:46That's the kind of minister I am. I would have a very small church. [laughter]

This conversation was about allowing your kids to be whoever they are and Sandra shared some things about her son, Kirby.Sandra:

I might have resented that Kirby was much sweeter, nicer, more mature, more sparkly when he was out with another family than he was when he was at our house. But I told Keith early on to remember that we were not raising him to stay home his whole life. We were raising him to go out into the world. And so I just saw it as a fascinating aspect of his life, and instead of complaining to him "Why aren't you nicer at home? Why are you so nice to them and not nice to us?" I didn't. I didn't talk to him about it at all. But I watched him. It also meant he was relaxed at home. He was able to see home as the place where he could shut down, turn it off, recover from the way he was in public.And he was not dishonest. He was just extra sweet, extra courteous. And I think that some "good parents" would have complained about that. They would have said, "Well if you have the ability to do that, you need to do that at home, too." But if I had ragged on him about the fact that he was less impressive at home, it would have made him probably even more irritable at home and more happy to be out. And as he grew up, I saw it more and more. He was working at a gaming shop when he was 14. He was teaching karate when he was 17, and working with younger children and just being the kind of guy that little kids would follow around.

We went to a Weird Al concert one time and we were in the big convention center So there are all of these areas inside, but not in the concert hall, where people are hanging around, and the have the t-shirts for sald and the CDs. And we're out there, and of course people are all excited to see Weird Al, but there was a whole dozen kids who were really excited to see Kirby Dodd. [later note from Sandra: They were excited to see him outside of the gaming store, where they figured he lived.]

He just wouldn't have blossomed in his own natural way if I had tried to make him be some sort of tree he wasn't. Trees grow from their seed. Acorns grow oak trees. Apple seeds grow apple trees. And sometimes parents think that by some sort of pruning, and you know, shaping, that they can change who their child is. But that's not being a good parent any more than planting trees and then not watering them, or letting the cat scratch them up, or whatever, is being a good arborist.

It's good to give them what they need, but to try to change them by withholding or shaming doesn't work any better for a child than it does for a tree.

6:17

Amy:

I thought I was going to do some episodes about parenting myths—something like that. So I asked Sandra some questions along those lines.Sandra:

There are sayings that people repeat that they've heard, that their parents repeated because they heard, and one of them is "I'm not a short-order cook."9:17"I'm not going to be a short-order cook." (on my site: Myths too many parents believe)

And what it means is "If you don't like what I made for the whole family, then you can be hungry 'til tomorrow."

That's not anything you would say to a guest in your home. It's probably not even anything you would say to some homeless guy you offered to feed if he said, "Oh, yeah, I'm homeless, but you know, I'm Jewish. I don't want pork chops." You'd probably say, "Okay, I'm sorry. Here—have a peanut butter sandwich."

But people do that to their own children, that they're supposed to really love!

I think it's healing when they make an alternative, when they know in advance that they have a kid who doesn't like spaghetti or spinach and they just don't even bother to try to give them that food.

If the purpose of food is nourishment and nourishment also involves the presentation of it, and the love, then it's not nourishing if you put some inedible thing there and say, "If you don't like it, be hungry.."

Instead of the parents clinging to their right to not be a short-order cook, they should look at what that means, and why would somebody have said that to them, and undo that hard place inside them. And offer people food that they like.

Short-order cooks actually exist. Every cafe, every diner—there really are people who look at a little piece of paper and go, "Oh. An omelet without cheese, da da da, da da da," and they make it in a minute. It's a skill. It's fantastic. Why wouldn't a mother do that for her children? I think it's kind of cool.

And it never involves being a short-order cook anyway. They're not frying and grilling for everybody in the family. They're offering alternatives. Sweetly. Nicely. As though they love those people.

I have a collection—kind of a tacky rude collection—the only rude thing in my whole life [Amy laughs] SandraDodd.com/support. Everything in there was actually written by a parent to another parent as what they hoped would be advice. And some of them say things like, "Follow your heart."

"Follow your heart" sounds good. It's kind of artsy, you know. It would be good embroidered on a pillow, but it doesn't make any sense. When someone is having a hard time with their kids at home to the point that they would go on the internet and ask strangers for advice, for help, "follow your heart" is really bad advice. I mean okay, well, their heart told them to go ask people for help.

If your heart isn't logical, don't go there. If your heart is working from those old messages from meaner older relatives, and you don't know how to be a nicer person, don't follow your heart. "Heart" in that phrase means emotion. "Just do whatever you feel like doing." But making a feeling decision can not only bring down the family and bring down that child's opportunities, but it doesn't help the parent to lay out their old wounds to dry.

Logic is good.

So if a parent knows that she wants to be kinder, gentler, more positive, more nurturing, there are things that she can do—little changes she can make and decisions she can make—that lead her toward that, and "follow your heart" is not a good one.

When people say "Well, I just followed my heart," sometimes that didn't go to a really good place because they didn't have a picture of their child's feelings. Coming up with a plan to logically step, step, step-by-step away from the dark confusion of people's childhood memories, hidden ideas, frustrations, fears—stepping away from that into the light is a better thing to do. And eventually they may get so good at this 'being more positive' that it seems like they're following their heart. But it needs to be their new, improved, mindful heart.

I asked Sandra what she would say to parents who want more alone time or "me time" or ddd time.Sandra:

It seems that the best thing a parent can do to feel whole and good and recharged is to be a really good parent. Because if they say, "This is frustrating me, and I feel crowded by you, and I don't like you, and I need to get away from you," and they go and they do some "me time," the child is wishing for the mom, doesn't know why she's been left alone. They're paying for their "me time" and they're paying for their babysitting and when they get back together, it's not as loving and smooth as it might have been if the parent had stayed and found a way not to be frustrated by the child—to love the child.Amy:

One absolutely fantastic shortcut, if your child is still young, is to smell his hair. And not like the ends of it and not like, "Ew, your hair is dirty," but to gradually, slowly find a way to be holding that child in your lap or hug him and put your face on his head and breathe. Because in that scalp smell of one's own children, there is a hormonal release of some sort.

When the mother gets away too much, the bond can break the same way school breaks bonds. School kind of needs to do it on purpose, because they want the kids not to cry. So they say, "It's all right, your mom's all right She's not missing you. She's busy, stay with us. We like you. Let's do this together," and after a while the child kind of gives up wanting the mom, and the mom—any mom who really, really wishes her child was home instead of at school—eventually kind of gives up that, too. Other people say, "No, no, I'm sure he's having a really good time. You need to be by yourself, anyway. You need 'me time'."

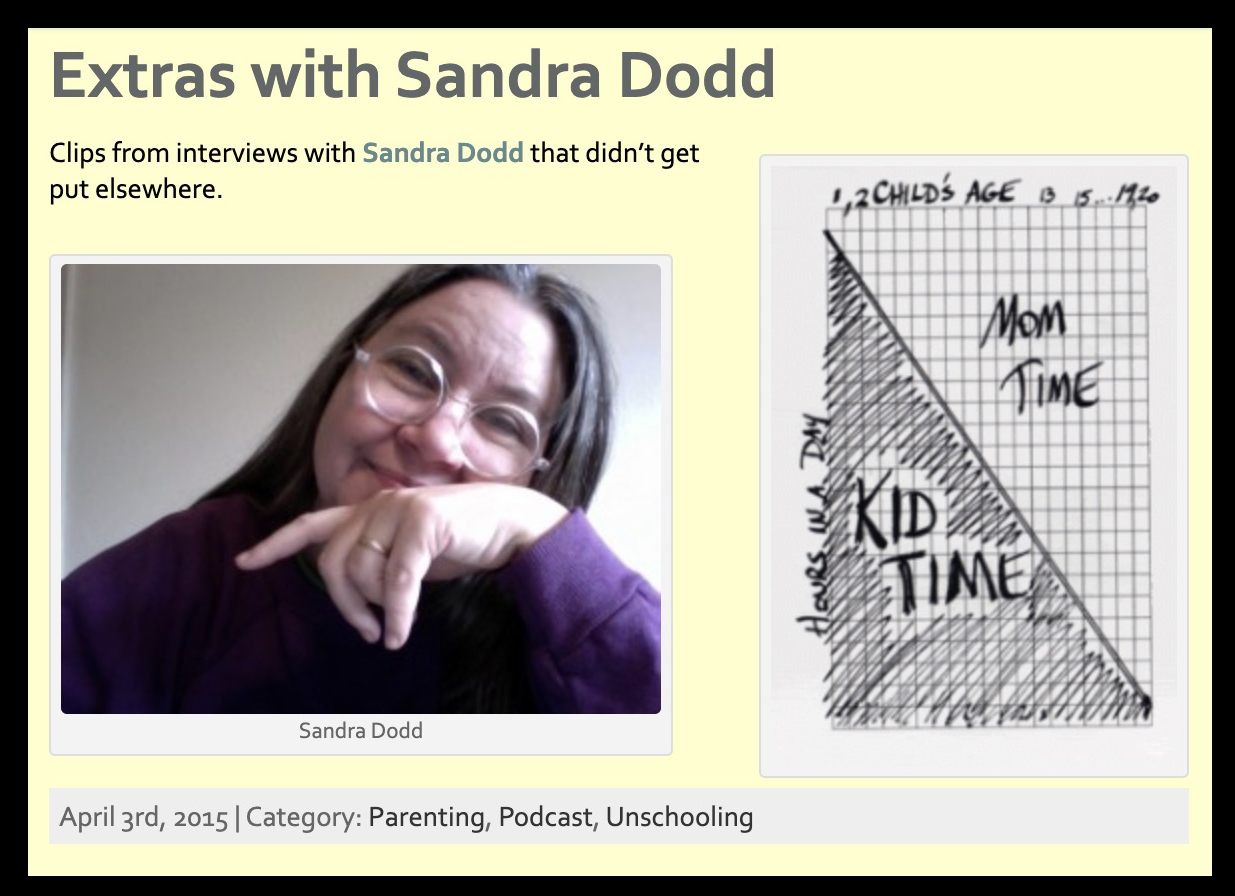

In the normal world, people sometimes think sometimes, "How little time do I really have to be with my children? What do I have to do? And after some years of people saying that, like, "Well, you know, is three hours enough? Is five hours enough?," I finally whipped out a Sharpie, and a piece of paper, and a pencil, and a ruler, and I made a graph that showed ages across one side, and hours of the day across the other side. So it went to 24 on one side and it went to 18 or something on the other, and I just drew a diagonal line.

When a baby's born, the mom can get one hour by herself without the baby, amd when he's 18, she needs to spend one hour with him. And I just drew a line between those and said, "There's your graph."

At first, it was kind of a sarcastic, you know, "Now stop asking," but the more I've looked at it over the years, and the more other people have looked at it and thought, "That's crazy. Oh, no... wait..." it does make sense. Because even when a child is two, you might get two solid hours of sleep, but you might not. And during the day you really can't expect not to be with a two-year-old all the time because they need you to be really close, so they don't get hurt, and so you can answer their questions, and so you can feed them, and hug them, and smell their heads.

12:18

When someone really focuses on what it would take and how they can make a few decisions to be a very present and very—I'll just say "good," because it depends what that person thinks of as good—if they want to be a really good parent and that's part of their goal, they seem to need less "me time."

I'll admit, I did have friends who would stay with my kids sometimes, and I would go to a movie with a friend, but I didn't say "Let's go to a movie in another town. Let's have dinner. Let's spend the night." I didn't do much of that for many, many years.

The more friends a person has with other children, the more opportunity there is to trade off kids. Like "I'm going to take all of our kids to the new Disney movie..." or to the zoo, or they can come over to our house and I'll make popcorn and we'll play board games. And if you can find another family or two to trade out with that way, where you keep their children sometimes and they keep yours, that gives you the adult time that a couple will need.

If you're doing family bed and a couple needs more time— here is a tangent

I said this one time in a discussion, and someone seemed disgusted, and thought I shouldn't say such a thing, but I said, "Stairs can be kind of fun."And sometimes they say well, I just need to really talk to my husband. So I want the kids to go to bed at 8:00 so that we have an hour to watch an adult movie, you know, talk about our days.And she was like "Why are you saying things like that!?"

Because you might want to have sex with your husband sometimes, and if you're not going to do it in the bed, there are other places. Or have more than one big bed—the one that you sleep in all the time and the one that's empty—conveniently empty—some other times.

Keith and I did that, did talk about our days, by email and phone while he was at work and we didn't watch adult movies together for a long time. We watched a lot of kid movies. We became familiar with the shows that they liked. Keith can sing all the songs. But he was already that way. He could sing The Jungle Book before I ever met him.

Later note, 2023. This has been sitting here with "an adult movie" playing, but I wanted to note that I didn't mean what it sometimes means. I meant a movie the kids wouldn't care about or like. Talky, maybe adventure, mystery, romance, no dogs or slapstick. That's all. 14:06

If the parents separate children's things from adult things, that by itself is a problem. If they say, "We need adult time, adult movies, adult food, adult whatever, and our children need theirs, and we don't want to be so much a part of that," unschooling won't work as well as if they see a movie that their children like as something they could also enjoy.

14:30

There's a little phrase I made up for a talk I did in Montreal. I wanted to do something new, for these people in Montreal. And so I came up with a talk based around advising people to read a little, try a little, wait a while, and watch. And that method—read a little, try a little—is the way people can come to understanding. Not "read a little, go crazy." Read a little, try a little, and then wait a while. Don't try it for twenty minutes and come back and tell us it didn't work. Wait a while. And watch what happens—watich how your kids respond. Watch how you feel about it. So it's take a little bit—actually try it in your life, and be an analytical observer. Now come try a little bit more.

15:15

If somebody said, "I want to walk to Santa Fe from Albuquerque," it matters which direction they go. It matters that they have water. It matters if they know how they're going to go. You can die between here and Santa Fe—it's a frickin' desert.

People can ruin their lives with unschooling if they don't know where they're going. If they just intend to make a bunch of wild decisions and mill around, it won't work. Their kids will end up needing to go back to school, and being clueless kids in school. So it's almost that big a project. You will have to take hundreds of thousands of steps. And so it's better to take a step thoughtfully, knowing what direction you're going, than to thunder around yelling, "I'm an unschooler! I'm an unschooler!" and not get anywhere.

So I think they need to understand the direction they're going, and why. And they can get there a lot faster and a lot more whole, and with a lot more peace and understanding, if they will Read a little, try a little, wait a while and watch.

16:07

So they say, "Okay, well I have heard and I've read that people have done... something? and then they get good results?" That's not enough to move on, but it's enough to read a little and try a little. Because they've seen other people say it worked, they can start trying it. And still they ought to be skeptical. Everybody ought to be skeptical about anything this crazy. So see how it's going at your house. Tweak it. Move more toward a good relationship. Move toward being more present, and then you start to understand. Then you start to be one of the people who's saying, "I tried this, and this was the result I got: my kids seem to be getting along better. My kids seem to be interested in more things. They're curious. They're conversational. They can deal with younger people, and older people."

And when they start telling stories like that, new people start hearing that and they kind of have faith in what that person's saying.

16:54

So we're moving along kind of as a crowd, as a wave, where the newer people have faith in the people who have gone before them on the trail, as it were, which is starting to be a pretty well-lit highway. But first it's just faith in other people's reports. Then you start to have some reports. And at some point it goes from being faith in other people's reports to your own belief, and it can move along from belief to conviction, when you've seen some big things happen, like your child learns to read without being taught, your children grow up to the point that they can really interact with other people, with new people, with older people, with professionals. That's not something that school kids are expected to do. They're expected to stay with the kids their age, not bug anybody else, mind their own business, and do what adults say.Of your own certain knowledge 17:45

So when you start to see the differences in your own life with your own children, then you know what you're doing, really, about unschooling. But from the very beginning if someone vaguely hears that unschoolers don't have bedtimes, they shouldn't go home and say, "If we're to be unschoolers, we must abolish bedtimes." If they don't know why, and they don't know what they should be expecting to see, they shouldn't do it. Maybe there was a time when I would have said, "Well just try it and see," but now I'm like, "Just try a little bit. Let them stay up ten more minutes. Let them stay up half an hour, or say, 'Friday night if you want to stay up all night, you can, because we've got nothing going on Saturday'." But there should be no All or Nothing in anybody's life. It's not a good balance. If you say "I used to tell you everything to do, and say, and eat, and I used to tell you what to wear, and how to sit, so now that is all gone," that's living a reactionary life. The child will react to that, and say, "Okay fine. I'm going to wear things you hate, eat what you don't approve of, and never sleep again."They think it for about thirty hours and then they sleep. 🙂

I think it's easy to jump too far and hurt yourself when you could have just taken baby steps, sat and rest a while, sleep, get up, take another couple of baby steps. You get there much faster if you haven't sprained your leg jumping.

I'm Amy Childs, and thanks for listening to the unschooling life podcasts.Sandra:

Read a little, try a little, wait a while, and watch.