Good day—for those of who don’t know me, my name is Phil Biegler, and I’m the proud parent of two unschooling children—Kimi, almost 16, and Shaun, 13. I’m also the lucky husband of Christine Yablonski, who has led me to this journey that we’ve been on for just over 6 years. I wanted to share with you some of the story of my transformation from a corporate, by-the-books kind of career-minded father into the radical unschooling Dad I think I am today. I also want to share how my experiences during my childhood and my early career ultimately helped me to embrace this wonderful lifestyle.

I’ve heard on numerous occasions that Dads really need to hear from other Dads, and I’ve come to agree with that view. I used to think it was a bit sexist—that the Dads just don’t get it, and that we’re a little dense. While this might be true for some of us, I think that in many cases the Dad is usually the parent who is working outside the house as the primary breadwinner, and the Mom is usually in the role as the primary care giver for the kids, and the journey into unschooling is started by the Mom. In this situation, the Dads have a different viewpoint. My experience is from this angle - obviously that of a Dad, but it’s really the experience of an out-of-house breadwinner who is being led towards the unschooling path. I hope other Dads in this situation can learn from my experiences. I hope that the stay-at-home parents can learn something from this story as well—gaining a better understanding of what might be causing some angst with their partners. For those of you who came to unschooling in a different manner, maybe story this can help you relate to some of what you hear from others like me in the community.

I want to start the story by talking about my childhood—I think this helps to explain where I started developing some of my parenting values. I grew up in Brooklyn, NY, in a neighborhood that didn’t exactly qualify as the best neighborhood in the city. For those of you who are familiar with NYC, I was near East New York in the 1970’s and early 1980’s. NYC was in the midst of a terrible financial crisis—the city itself almost declared bankruptcy during that time. Services were cut dramatically, and the schools were not spared. I remember when I was in 6th grade that the school day was shortened by one and a half hours per day, two days a week—a concession to the Teachers’ union for the cut in pay that they had to endure as part of the crisis. Class sizes were up over 30 kids, and textbooks were hard to come by.

For those of us who dreamed of escaping this area in good shape, school was our way out. My mother was on public assistance, and that’s how she supported me and my three brothers as a single parent. Truth be told, school was both an experience to be dreaded and an escape from my home life. It was two meals a day—breakfast and lunch—school food, which I think helped contribute to my cast iron stomach, as well as to my incredibly boring palate. My mother was both mentally and physically disabled—although I didn’t fully understand the mental disability until I was a teenager. She was intelligent—I still remember asking her all kinds of vocabulary, spelling, and history questions, and I don’t remember any of her answers being wrong. However, she imposed some pretty arbitrary rules on us. For example, in general, we were not allowed out during much of the day on non-school days to play with friends, and we weren’t allowed to have friends in the house. I can remember sitting for hours at a time near my window with friends outside, talking to them, occasionally being ridiculed for not being allowed out. Several of my closest friends went to parochial schools which started 30-45 minutes earlier than the public schools. In order to spend more time with them, I’d get up early on school days to walk with them to their school, then turn around and walk back in the other direction to go to my school.

I did pretty well in school, and showed some promise in math. I was encouraged by several teachers in the school to pursue some sort of science field. I distinctly remember being asked at the end of 6th grade by a science teacher if I had any career interests; I remember saying “maybe a policeman, or a fireman”—after all, I was 11—and having that teacher try to talk me into going into a science field.

This being NYC, and different from everywhere else in the world, we all had big decisions to make as 8th graders—what high school did we want to attend? At the time there were about 75 specialized high schools that were open to many or all residents of NYC. You could find a school to specialize in just about any kind of career—there was one high school for aviation mechanics, and one for pilots; one high school for pre-veterinary studies, and one for farming. There were also the ‘exam’ schools—a trio of technical schools that shared a single entrance exam. We had guidance counselors in junior high school to help discuss high school choices. I took the ‘exam’, and was admitted to Brooklyn Technical High School—team nickname, the Engineers. So, here I was on the science/engineering track that my 6th grade science teacher thought I should be on.

I loved high school! Almost everyone who was there chose to be there. Most of us had the same goals and interests. Students came from all across NYC; there were only 2 of us from my junior high school who went to Brooklyn Tech, so it was a chance to ‘start over’ for many kids. It wasn’t perfect—but still I looked forward to school most days since it was still a nice break from my home life. Now that I was older, I wasn’t subjected to all of the arbitrary rules of my mother, but it was still a tough place to be. I went out when I wanted to, choosing to spend as much time as possible away from home, but I also wanted to help raise my younger brother who was 5 ½ years younger than me. We moved to a new neighborhood after 9th grade, and that helped to change things a bit. At the end of my sophomore year, I chose my major—aeronautical engineering. I don’t remember why—mostly, it seemed interesting. By the end of my junior year, I realized that I wasn’t really passionate about aeronautical engineering, and I prepared to change to the generic ‘college prep’ major. This is when my life got really interesting.

I need to flash back to my elementary school years. My 6th grade teacher—Mrs. Miller—had taken a liking to me as the year progressed. The school tended towards the underperforming side, and I had shown this academic promise. I also had a mother who was, as I mentioned earlier, not in the best condition. Our family was known by the administration in the school—due to some of the mental and physical disabilities suffered by my mother, we had been in and out of foster homes and children’s homes, and we had multiple tours thru the school. Plus, I had two older brothers who preceded me, and who had done well themselves. Mrs. Miller had been in the school for more than 10 years, and had heard of our family and knew of our situation. The summer after my 6th grade graduation Mrs. Miller invited me to spend a weekend with her husband and family. They had two children 3 and 4 years younger than me, whom I had met several times when they accompanied Mrs. Miller to school. It was a wonderful escape for me, but it was an awkward situation for all. There were a couple of other visits during 7th grade, but we lost touch within a year. Now flash forward to the end of my junior year in high school, when I was in the process of changing my major, and when for some reason I decided to go back to my old elementary school and visit with Mrs. Miller. We reconnected, and I once again went out to spend time with her family. We talked about my situation in school with my desire to change majors, and to move more towards a less technical field, maybe history or psychology. She suggested that I go into the computer field, as her brother had been working with computers for a few years and really enjoyed it and saw it as a growing field. So, I made the decision to stick with aeronautical engineering in high school, but to look for a college with a computer science program.

That same summer saw even more upheaval for my family. My oldest brother was killed in a freak car accident at the age of 19. My mother’s mental state took a turn for the worse, which resulted in her taking out some of her grief on me. Her actions were irrational, and I wasn’t interested in putting up with this behavior. Partially as a result of this, I grew closer to Mrs. Miller’s family. I spent half of my senior year in high school living out on Long Island with the Millers and commuting into Brooklyn to school. This was the beginning of my change to a new family—a new Mom, Dad, brother and sister. A parallel family of sorts—a major change in my life and the source of confusion and humorous stories for years to come.

With the help of my new family, I went to Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, New York, where I majored in computer science, just as my new Mom had told me to. I had a fantastic time in college. One of my most important personal decisions in college was to join a fraternity—Lambda Chi Alpha, for those of you who might have been in the Greek world. It was important for several reasons. First of all, it helped to provide me with a positive identity—I was a Lambda Chi; second of all, it encouraged me to participate in activities that I wouldn’t have otherwise; and maybe most importantly, it allowed me to influence and help others in a positive way. I have many fond, fond memories of college. I can recall a couple of events that, in hindsight, were telling for my journey towards unschooling.

First, I was (and still am, for the most part) a non-drinker - a well-known fact at the fraternity. This was back in the days when we had a keg on tap in the house, and a signup sheet on the wall, and we billed you 25 cents for each 16 ounce cup at the end of the month. Most students in my year and above were of legal drinking age (the drinking age in NYS was 18 at the time I started, 21 by the time I graduated). I lived in the fraternity house for 3 years and I never had a single beer charged to my account. I used to go out with the brothers to the local pubs for cheap meals, and I’d always order a Diet Coke. I noticed over the years that it went from me being the only one in the group not drinking beer to me being one of several not drinking. In many cases, guys went from being drinkers to non-drinkers over the years. Turns out that peer pressure had gotten the best of them initially, causing them to join in on the beer drinking. Now they were able to join me in refraining.

A second memory was from when I was President of the fraternity and involved one of our underclassmen, Mark. He was having troubles with his chosen major: engineering. He was smart, and he was good with math and science, the necessary ingredients for a good engineer—but it turned out that he didn’t like engineering. He was there because his Dad was an engineer, and he had other engineers in his family. He was into music—he was a DJ at the school radio station, and we counted on him for music at our parties. We had a long talk one night, and I gave him some advice from the heart—get out of engineering, leave RPI if necessary– but go do something you like. I told him if you’re passionate about something, go pursue it. Sound familiar??

Soon after graduating from college, I started a job at an investment bank in NYC. I was officially on the corporate ladder; in fact, by virtue of the special “Information Systems Leadership Training Program” that I was accepted into, I was on the fast track. This is what I had spent the past 16 years of my life working to achieve—and I was quite happy with it. For a little while, it worked out just as I could have hoped it would—as part of that training program, I attended structured classes and took exams, and learned as much as I could. At the end of the program I finished near the top of the class, which allowed me to choose the department I wanted join. I was on a course that encouraged 12-14 hour work days, quick advancement, bonuses, and challenging work. I was able to double my salary in 2 years! We were doing some complex work—ground breaking technical work in some cases—and the core values of the organization included “thinking outside the box.” We were encouraged to come up with new ideas—because the old ones were not the best way for the business to move ahead. We all worked hard to “think outside the box.” It didn’t occur to me at the time to ask “who created the box?”

A little digression about this Leadership Training Program. It was unique on Wall Street. Most people on Wall Street were business types with business degrees from business schools. The Information Technology area—the computer department—was relatively new, and was creating a competitive advantage for some banks. Morgan Stanley, the bank I worked for, had this great idea: create a prestigious program with the goal of attracting top talent from the top universities, regardless of their major. In fact, for the first 5 years of the program, there were no computer majors at all—they had biologists, journalists, and my all time favorite, someone with a PhD in theoretical linguistics. The rationale was simple—get people who were high achievers in what they had pursued, convince them that this was something worth pursuing, and then let them go at it. It was a very successful program—but it had its limitations. Half the participants in any class were generally gone within 2 years of graduating from the program, and at least 1 person in each class didn’t make it all the way thru. It turns out that encouraging someone to believe that this was his or her passion wasn’t as successful as one might hope in having this actually become someone’s passion. A little foreshadowing?

OK, back to my story. I started to experience more and more of the ways of the corporate world. I asked questions of those in charge, and tried to connect with and emulate those who I liked and thought were successful. I had minored in management at RPI, and I was interested in the management aspect of some of the higher positions within the company. My first foray into management was when I was 25 years old; I was somewhat abruptly put in charge of a team of 2 people due to staffing changes. I was given no real training or guidance—just a mandate to keep the systems going. I took it upon myself to try to figure out the management thing by taking the time to imagine, “hey, how would I want to be managed?” A couple of years later I had the opportunity to move to a different group and started managing a larger team. This became one of those big “A-ha!” moments in my career. Let me explain.

This new team was a classically underperforming team—poor morale, high turnover, negative attitude, and low productivity. I had previously had some dealings with them, and liked many of the people on the team, but I knew their reputation. I got down there - it involved moving to a new building—and started spending time with the staff. Turns out that I was the first manager they had who asked them what they thought about the performance of the group. Basic Management 101, right? Ask the people on the front lines for their thoughts, and get insight that you could never imagine! Within 6 months I retooled the group—helped some people find more suitable positions within the company, where they would be happy, and replacing them with folks who were a better match for the job at hand. We went from 50% turnover every 6 months to 25% turnover in 2 years; saved the company tens of thousands of dollars per month in performance improvements, and improved customer service dramatically. How’d we do this? I listened; I let people do what they wanted, in the context of the business; I found ways to say ‘yes’ instead of ‘no’; I didn’t punish failure as long as it was in the pursuit of the business, and I treated everyone as equally important. I didn’t tell my staff that they had to be better at what I wanted them to do—I helped them find what they wanted to do and helped them improve.

This experience also helped me to realize that someone’s ‘pedigree’ was less important than their passion and experience. In several instances, I replaced top graduates from top schools with people who had fewer academic credentials—but far more interest and background. I have stayed in management, with a few short breaks, for the 15 years since I left this group, and I have used this lesson extensively. The performance of my staff members was not correlated to their education level, or their standing among their classmates, or the caliber of the school they came from; rather, their performance was correlated to their passion for their profession; their motivation to improve their skills and abilities; and their perception of the support and encouragement they received from their management.

When Christine was pregnant with Kimi, our oldest child, she got involved in La Leche League as a strong proponent of breastfeeding. This was my preference as well, so we were in synch with that. We were still in NYC when Kimi was born in a hospital setting. It was pretty normal—easy for me to say, labor didn’t hurt me at all—and we had her crib all set up at the apartment, and worked out a pretty standard process and schedule. We kept a list of every time she nursed, for how long, and every dirty diaper, so we could make sure she was developing within normal ranges. I used to get up in the middle of the night, bring her to Christine in bed to nurse, and then bring her back to her crib. A combination of laziness and weariness set in, and sometimes Kimi didn’t make it back to her crib—she just stayed in our bed. How convenient!! I got more sleep, Kimi cried less—many of you know this story. With baby number two—Shaun—things were different. He was born at our first home in Massachusetts—15 minutes after the mid-wife arrived. No more lists—for those of you who know my 13 year old man-child walking around, you know he got enough to eat! And he spent a lot less time in a crib; in fact, we completely embraced the family-bed concept!

So, breast feeding, check; attachment parenting, check; now, let’s send the kids off to school all day long and leave the rest up to someone else!

After briefly considering Montessori schools, Kimi and Shaun entered the public school system. The elementary school in town had a nice program that combined 1st and 2nd graders in the same classroom. Kimi was chosen for the program, and had a nice time there, enjoying having the same teacher for 2 consecutive years. But this is also where the troubles started.

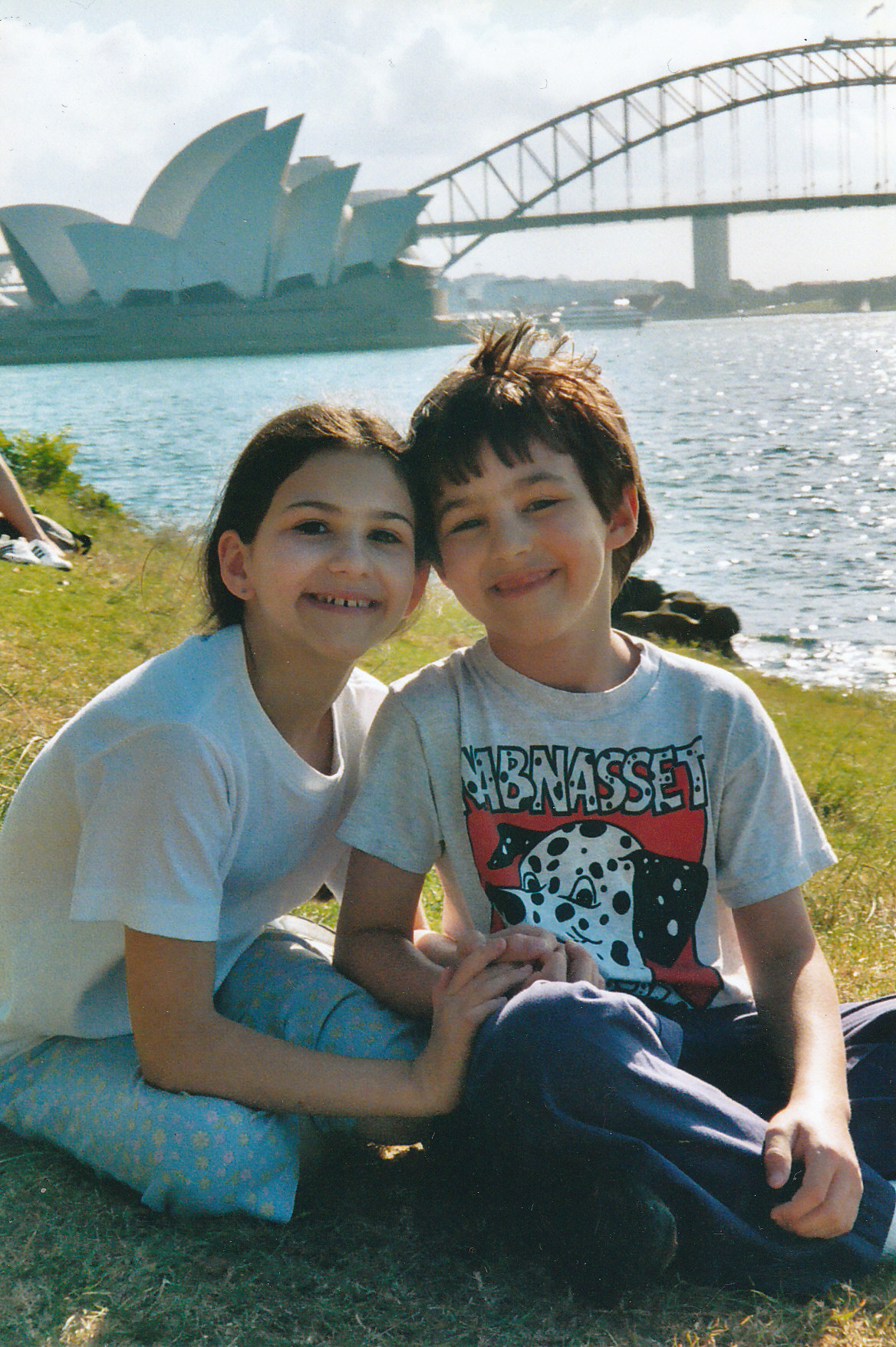

The last straw was perhaps not the most dramatic part of the story. I had an opportunity to travel to Australia for business & we decided to include the whole family. So, we planned the trip, a 2 week vacation (including 5 days of work for me) in April, with one week coinciding with spring vacation. We went to Kimi’s teacher and explained the situation—we were taking Kimi out of school for a week to go to Australia. We asked if we could get her homework to take with us—the response was “No, that’s against school policy, she’ll have to make it up when she gets back.” OK then—maybe we could substitute homework for a show and tell—we’d work with Kimi to put together a nice story on the trip, and have her present it to the class. “Oh no, we’re not studying Australia this year.” Huh? What year is Australia in the curriculum?? How many of these kids and their families would ever get the chance to go to Australia?? Clearly, the purpose of school was not to act in the best interest of the kids.

We’re out of here!!

We made the decision to pull Kimi out of school at the end of the school year. Shaun had just finished the first year of the same 2 year program Kimi had been in, and we wanted him to finish the 2nd year. Well, I wanted him to finish—Christine wanted him at home. Guess who won that argument??

We spent a lot of time during the summer talking about homeschooling. My concerns were around curriculum, and measuring progress, and making sure they didn’t fall behind. Christine’s concerns—well, she wasn’t as concerned. The kids would learn, and they’d be fine. She started telling me about this ‘unschooling’ idea—and I thought, whoa, that’s going just a bit too far out on the edge. So, we just let the kids do what they want? How would we know they were learning? Would they be keeping up with other kids their own ages? I think most of you know the questions that were going on in my head—they are the same ones that either you or your partner experienced, or a family member shared with you.

As the summer progressed, a couple of ideas started to dominate my thinking. First, I started to think that there isn’t much that we could do to the kids that would truly ‘break’ them—I mean, if I survived what I went through in my childhood, how could taking some time off of school harm Kimi and Shaun? Worse case, we put them back in school, and years later this little experiment never happened. This thought, I think now, was just a little bit of rationalization to help me feel better. The more important idea was that of trust—Christine had a background that was focused around children; she and I had similar parenting styles; she had done a lot of research on this topic; and she had been the primary parent raising our kids. I trusted her! So, if she thought this was going to be best for our kids, then I should start from the premise that it would be best, and work from there. Whew! Problem solved, right? Well, not exactly. See, I still had all the same nagging questions—how will I know they’re learning, how will they be ready for college, how will they support their own families, etc., etc., etc.

So then it turns out that Christine discovers a conference that is scheduled for August, right in Peabody, Mass, about this ‘unschooling’ thing she’s been talking about. “We should go!” she said. So we attended the conference (“Live and Learn”), and with the kids being 7 and 9 years old respectively, I spent most of the time watching them while Christine went to the talks and lectures and discussions. I felt that since she was going to be presiding over this ‘unschooling’ effort that she needed to get the most out of the conference. I have to admit that the conference didn’t really help me much—but it really helped Christine, and that was the most important aspect to me. Christine felt that she had seen proof that kids who are unschooled end up just fine—so she felt more convinced that this was the right decision for our family.

We spent the first year as unschoolers in the way I think is not unusual in this situation. I would head off to work early while everyone was still asleep. I would arrive home after a long day at work, and trying to be engaged, I’d ask “so, what did you do today?” After that conversation ended, I would proceed to do some of the evening chores—tidy up, dishes, you know, the usual. Those of you who are the out-of-the-home breadwinners know this scenario—after a while, I couldn’t ‘see’ what was being accomplished, and even though I wanted to trust that everything was all right, I wanted some sort of proof. This was a difficult time for me. I felt like I was working hard—55-65 hour weeks, commuting, doing chores—and I’d come home and Christine and the kids had slept till 10am and spent 4 hours at the book store. Then the weekend comes, and we’ve got work to do around the house—yard work, clean up—and the kids would sleep till 10 or later and then watch TV. Some days were tougher than others for me. Christine and I talked a lot, and she explained ‘deschooling’ to me, and I tried to be patient. Of course, being the busy Dad, I didn’t have time for the message boards and the groups and posts and the rest of the online support community, and I wasn’t interested in spending more time on the computer after a full day’s work on the computer. I saw what I saw, I listened to Christine, and I went about my routine, which wasn’t much different from when the kids were still in school.

Actually, there was one huge difference in my routine—the mornings. I no longer had to get Kimi out of bed at some ridiculously early hour to get on the bus. My mornings were bucolic compared to the past 2 years. My daughter was a much, much happier person. I also didn’t have to worry about whether they were doing their homework at night—again, an increase in the family happiness factor.

By this time I had been working at RSA Security for 7 years, and was pretty well established there. I was in a management role again, and this time I had some pretty high powered technical talent working in my group. This was the ‘knowledge workplace’ - where the technical staff was much more knowledgeable than the management staff in their areas of technical expertise. I was very comfortable in this situation—my staff knew things, and could do things, that I could not. I was not their boss because I could do their jobs better than they could, but because I was better at being a manager, a leader, than they were. In short, it wasn’t uncommon for me to admit that I didn’t know something, and seek answers from them.

It also wasn’t uncommon, since I had worked with some of these folks for 5 or more years, to talk about our families—and so, I started talking about homeschooling our children, and for those who cared to know, I would explain that we were unschooling. So, here I am, in a group of highly technical folks, most of them parents, nearly all of whom had at least a bachelor’s degree. You can imagine the questions—and here I am, not completely bought into the concept in the first place. So, when people asked me “how will you know if they are ready for college,” my honest answer was “I’m not sure.” When they asked if the kids would ever go back to school, I would say I didn’t know. This went on, and on, and on—and while I didn’t feel a need to convince anyone that my way was the best way and that what they were doing was wrong, I also didn’t need to back down. I was honest—no reason not to be; I wasn’t worried about what they thought of me—these were folks I had known for a while, and with whom there was a mutual respect.

Over the next couple of years I continued to struggle with some of the same issues and concepts, but I also started to expand my understanding of unschooling. I’m struggling with a number of things. I spend my day in a corporate office, dealing with professionals, all of whom have college degrees, all of whom send their kids to school, in a very structured environment. Just like I did before we unschooled. This day lasts 9-12 hours, including the commute, surrounded by the rest of the schooled masses. I get measured by my accomplishments; and in order to avoid potential lawsuits, I have to judge my staff equally, against objective measures. It’s been like this for me for years. I’ve thrived within this system; it’s done me well. I remain the only breadwinner for the family. If we need more money, I need to work harder. Or longer hours. Or more years. And, while I’m enjoying hearing the stories of how Christine and the kids are doing things they love—reading, art work, projects, field trips, discussions, travel—I’m thinking about how far away my retirement years are, when I can finally do all the things that I want to do.

I’m also attending more conferences; spending more time with other unschooling families; reading more about unschooling and the experiences of others; seeing my kids thrive, grow, and develop; and observing some of the challenges that kids in school are having. Slowly, gradually, I’m getting more and more comfortable.

One challenge, as I shared a little while ago, was that while our family life changed, my life didn’t change very much. Another was that while Christine’s and the kids’ lives changed, some of their expectations about our financial situation didn’t change. Yet another was that for a while, our lives diverged—we grew further apart instead of closer together. And last—well, I’m a guy, and that means I have some challenges that are endemic to my gender. Let me explain these a little more.

My work days, and so much of my life, didn’t change drastically from when we had the kids in school. I do feel like I was enlightened by this unschooling path, but I couldn’t see the full picture. My life was still rooted in that corporate world, and I was doing pretty well. And while Christine and the kids were leading this unschooling life, they didn’t change their expectations around what we could do and afford. We had a pretty nice home in a nice town with some nice things, and now there were more opportunities to travel, take field trips, eat out, shop, and explore their passions. This included purchasing books, and craft materials, and toys, and video games, and iPods, and—well you get it. Now, don’t get me wrong, I’m not trying to point out a flaw; let’s face it, we were living in suburban Boston, and I had a nice job in a high tech company, and we were in a position where we got a house we liked in a town we liked, and we could afford to do some things we wanted. But when you put these together, you could see that the pressure on me as the breadwinner didn’t change. It didn’t really occur to me to ask them to change their expectations—the reality is that only a pretty drastic change was going to make a real difference, and none of us were in a frame of mind where we could just up and move, I don’t know, to somewhere like Asheville, NC, and start over again. Our lives were in Westford, MA, and we were quite happy with that.

Let’s not forget that the kids are ‘deschooling’ at this time—and the right thing to do is to let them handle things in the way that was best for them at their own pace. This was all new to us—we had never seen deschooling that up close and personal. Here are some of the natural consequences for me to all this—I’m staying close to my comfort zone to make things simpler; I’m struggling with this huge change in a part of my life, but not the rest of my life; I don’t have the same common ground with the kids, where previously at least I had the common experience of having gone to school, and I could remember some of the math or history or other facts that they were learning at the time. So, for a while, we started growing apart, living our separate lives, each ‘side’ not fully understanding what was going on in the other side’s life. Now, add to this fact that I’m a guy—and I’m generalizing here, so no offense intended—so I’m not searching out support groups, I’m not reading the message boards, I’m not getting books and magazines, and I’m not always sharing my feelings. At this point, I can only attend one conference per year—I can’t take as much time off work as I want to, after all—so my opportunities for outside guidance and help are limited. At the same time I’m trying to have a life. There are football games on Sunday, and racquetball matches on Saturday, and lots to do around the house and yard.

Oh, and add to this one other little fact—as I mentioned earlier, it was Christine who discovered and researched unschooling, and who was passionate about it. So I’m starting out a year behind her, and she’s moving faster than I am. So every day I’m just a little further behind.

As radical unschoolers, we had the extra effect of the changes in our lives being not only around the educational philosophy for the kids, but also for the way we lived our lives.

As an unschooling Dad, based on where I came from, and where I was spending most of my time, and where the rest of the family was at this time, I hope you can see that this can be a little overwhelming. Dual lifestyles, conflicting priorities, unanswered questions, and general upheaval in my life—these can all cause a bit of stress in one’s life.

I ended up doing a bit of soul searching during this time. I ended up taking a couple different approaches to find answers. One approach was reaching out to others in the unschooling community, especially the Dads. The ability to talk to someone who was able to say, “I’m in a situation similar to yours; I had the same concerns and questions; here’s what I’ve learned and realized over the years to see how unschooling works” is powerful. Additionally, talking to a variety of Moms, kids, and young adults, and getting their viewpoints and sharing their experiences, helped a lot. There were a lot of one-on-one conversations where I could share my concerns. There were also talks with others who were just starting out, and trying to assuage their concerns about unschooling helped me to realize the ways in which it was working for us.

Let me highlight some of the help that I received from my unschooling friends. During a couple of the early conferences, I was bugged by answers I heard from other parents to a couple of the questions that I think many Dads share. The first question was about the change in the lifestyle. In its simplest form, the issue was around cleaning the house—it used to get cleaned, and now it doesn’t. So I get home, after a long day at work, and the kids have been doing “whatever” and there’s a mess on the kitchen table and the living room looks like a toy box exploded, and the dishes are piled up in the sink. What to do? The answer I often heard from the other radical unschooling parents at conferences, and hated, was “You just need to get over it, and move on. If having a clean house is important to you, then you clean it.” Sometimes, the answer was “Let go of your pre-conceived notions of what family life is supposed to be—change your priorities.” Huh? What does that mean? I felt that was a brush off answer, and when I heard that answer in Dad-oriented gatherings (especially the SSUDs sessions) I could see the eyes rolling back in the heads of the newer Dads, or the ones who really had that question. It took me a couple of years to really get to the bottom of this one. You see, what I was really feeling was a couple of things—first, I was being left out of the amazing new lifestyle; second, I felt that I was now not a full member of the family. My needs were not being respected or met! So, as we were trying to follow this new lifestyle, allowing everyone to follow their passions, and not forcing any unnecessary rules on people, we needed to do this as a full family. I needed to find ways to participate in the lives of my family, and just as importantly—I can’t stress that enough—my family had to count me in as an equal, and my needs had to be just as important as theirs. Once this became clear to us all, we were able to get past it—because, you see, if it *is* important to me that there be some cleanliness to the house, then this need should be respected just as any other need. Just because it seems to cling to the ‘old’ way of life doesn’t make it less valid; after all, my life, by mutual choice of the entire family, is still dominated by this ‘old’ way of life. It took a little bit of time, but we got together as a family and talked. We gained a greater understanding of respect for each other. We focused on what was important to the others in the family—not questioning why, but acknowledging the identification - and then we worked to honor those needs. This helped all of us—not only did I find more of my needs being met, but we were all able to better meet the needs of the others in the family. It allowed us to be open and honest with each other. Things aren’t perfect, but they’re really good, and no one is ashamed to tell the others what their needs are and we expect that the others will do what they can to accommodate. This has allowed me to stop feeling left out (although I still don’t get all the inside jokes), and enjoy my time with the family more when we’re together.

The second question that still nagged me, and as I observed, nagged other Dads, was around the issue of our kids’ future employment. How do I know that my kid is going to be able to support himself as an adult? How would my child support her family? And how would I not have to work thru my retirement years to support them? Again, the answer was unsatisfactory—“trust your kids; by pursuing their passion they’ll make a living.” Sorry, but as someone who followed the school-college-corporate job path that isn’t very comforting. I’m thinking that no one is going to hire my son to play video games or hire my daughter to read Harry Potter books. Trust them? I trust them! What does that have to do with them being able to support themselves and their families? I continued searching for answers and I learned several things. A wise unschooling Dad—he’s not here at this conference, but his sons Cameron and Duncan are—shared some of his wisdom. The first nugget—most unschoolers would not be looking for a corporate job, but would be looking to become entrepreneurs. For that, they needed most importantly to find a passion, and then find a way, thru an apprenticeship, or an internship, or a partnership, or self-education, to learn all they can about that passion. Then, they can start their own business, or join an existing small business, to get to do what they want. The second nugget is that out of the respect and love that unschooled young adults share with their parents, they don’t want their parents to have to support them their whole lives—& in fact, they want to be self sufficient. Wow! These were breakthrough ideas for me! On these issues and others like them, the unschooling community really came thru for me.

The other approach I took to finding answers to the bigger questions was to make a series of observations of my life. I’ve shared some of the situations I experienced at work—especially as a manager. I started to see significant parallels between unschooling and successful management. I considered how I was treating my staff, and how I was making decisions and providing advice about their advancement, and I saw a huge convergence between my management principles and unschooling principles. Encourage people to follow their passions; provide different ways for people to learn; provide guidance, not lessons; treat people with respect; allow for different perspectives on how someone got right here, right now. All of these principles guided my work life, so how could I not see how they should guide my personal life? I’m not saying that I should treat my family as if they are my staff, but I am saying that I shouldn’t treat my work staff better than I treat my children. I am able to see the different context—I am looking to increase performance at work, but I’m looking to increase happiness at home. Still, the parallels are there.

During the six years we’ve been unschooling, I have seen the development of my children into happy, engaging, respectful, bright young adults. I have the pleasure of being with other unschooled kids, and we have a number of friends and family members who are not unschoolers, and I have seen the development of both sets of kids over the same period of time. I have, in front of my eyes, indisputable proof that unschooling works. I didn’t see all those concerns that I had in the early years materialize. Unschooled kids are just as ready for the adult working world as their schooled peers; in many ways, they are more prepared.

I hope that by sharing some of my journey into unschooling I have been able to provide some insight into some of the challenges faced by a specific group of us in this community. I hope this helps you understand why some of us are having these challenges, and I hope it helps to make the path easier for some of you.

Thanks for your attention—enjoy the rest of the conference!