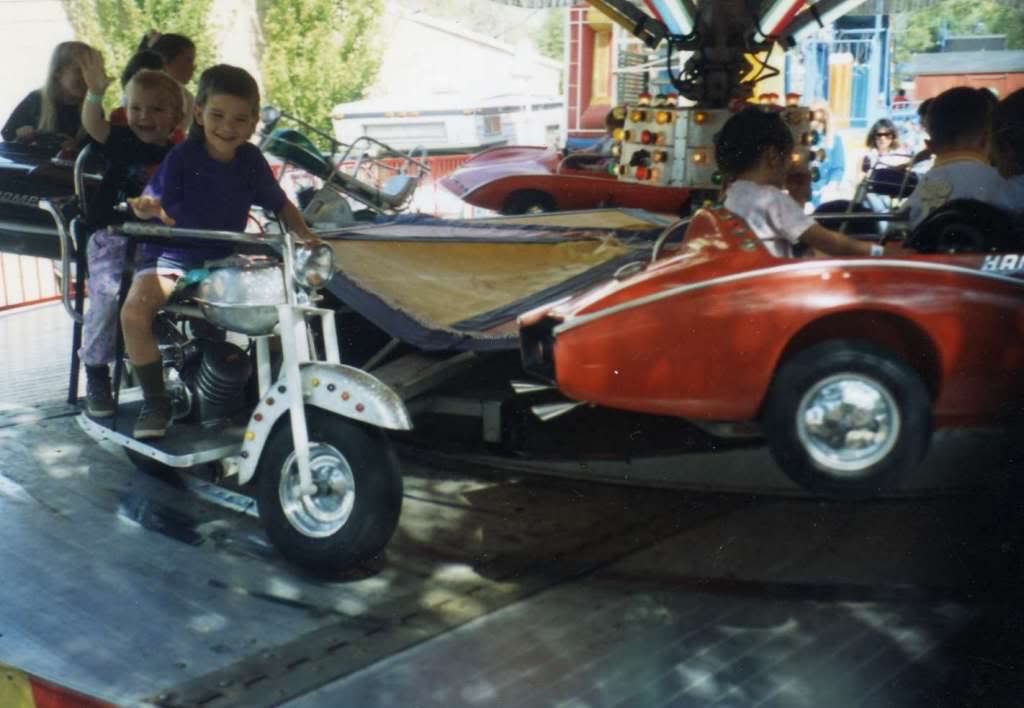

Kirby and Marty on a motorcycle at Cliff's

My first exposure to an unschooler in driver's ed involved Brett Henry, who had left public school partway through third grade and has been in and around our house and family quite a bit since then. Brett researched and chose a driver's ed school near our house. He was living nearly 50 miles away and couldn't be delivered back and forth, so he stayed with us and we took him to class and picked him up.

Brett's time in driver's ed was a learning experience for our family, too. Every day he told us what they'd done in class, and he critiqued my driving during the transports, which amused my own kids greatly. It was useful for all of them too, though, because I would explain why I had chosen to do what I had done, sometimes to great humorous effect.

Kirby started driver's ed classes late, for his age. Partly, he was worried he couldn't write fast or legibly enough to take notes. Partly, he had older friends driving him anywhere his heart desired, day and night. Partly, he worked four or five days a week and went to karate twice and didn't have time to schedule a class.

Finally, when he went, he was nearly seventeen. That was his first day of school, ever. He took an apple and gave it to the teacher saying, "I've never been to school before; I understand this is what people do."

On that first day there was a pre-test with a question booklet and a separate answer sheet. Kirby was circling the letter and then writing out the right answer.

When the teacher asked if everyone was through, Kirby had three more left and said he was still writing. The teacher said "writing?" So his only problem with driver's ed was his total unfamiliarity with the traditions involved with test-taking. He got seven out of ten. He missed one about hydroplaning, which he said wasn't worded well to get the answer they wanted. I doubt that many of the other kids were analyzing the construction of the test questions.

Marty, like Kirby, was good at asking questions in class and caring about the answers. They were better than most at participating when there was something interesting to do (such as get into the cab of a semi for a demonstration, which Kirby did without hesitation, but the other kids were too cool to want to do).

In that season, someone who didn't know better wrote on a discussion list and assured us that unschooled kids would be totally unprepared to go to classes—they wouldn't be able to wake up and get to a class on time, to take notes, to take a test or to write an essay. I knew from my experience with Brett, Kirby and Marty that they had no problem showing up early and well-prepared, taking notes, participating in class or driving.

As I write this, Holly is fifteen and in the midst of her second week of the classroom portion of driver's education. The first day she was a little intimidated about note-taking. She came home and asked Kirby if he still had the notebook he and Marty had used. He knew exactly where it was on the shelf in his room, and so she has taken that every day since. She finds where Kirby or Marty took notes for that chapter, follows along, and writes down anything they missed that she'd like to remember. Now the notebook will have the notes of the three of them combined.

Holly could have been finished by now, had she been willing to go to class on Halloween, but she's always loved dressing up and going trick or treating and had already made arrangements with friends, so she opted to wait until the first session after Halloween. Her desire to dress up and frolic outweighs her hurry to drive.

As was also true with her brothers, she's not the only homeschooler in the class. It's not as homogeneous a group as she had expected. Besides another homeschooler, there is also a girl in Palestinian dress and two exchange students from Germany.

Holly likes the class and is always eager to go. She enjoys the different styles of the two teachers she's had, and the movies, and the other kids. She has fun taking notes. When we're on practice drives, she tells me the stories she's heard in class about freak accidents. She got to sit in a semi, as Kirby did years ago, and heard stories of runaway truck ramps and about some dangerous and safer ways to park on the side of the highway.

Just a few hours into her required fifty hours of practice, Holly is already a confident driver. Her time with Brett, Kirby and Marty, as they went through this process, was clearly a time of learning for her. She refers often to things they said or did.

The carseats are long gone. Soon the requests for rides will be gone too. The learning is thick, and rich, and fast, and because of Holly's unschooling life, she doesn't consider stories from the certified driver's ed teachers to be more valuable than those of the guest truck driver, or her dad, or her brothers, or their friend Brett.

It's not only the notebook that bound these experiences together. Even though they didn't attend the school at the same time, my three and Brett have a sense of sharing and camaraderie about their learning to drive. They've watched and helped each other for years. Each of them had fun with the course, had great stories about the teachers and the practice driving, and they've left good impressions about homeschooled kids at the school, too.

One day while Holly was in class, Marty got a call to come and rescue Brett, who had been in an accident across town. It was someone else's fault entirely, and he was uninjured, but his truck had to be towed. Their shared learning continues.

Those who were once my three little babies are about to be my three drivers' ed graduates. Marty was talking about the possibility of driving to the Live and Learn conference in North Carolina next fall, just he and Holly, because she'll be able to drive by then. I think they'll fly to Florida and ride with another family, but just discussing it with him changed my perspective as a mother. Everyone is happy, but there's a little sorrow in the mom whose last child is about to drive away.

Sandra Dodd lives in Albuquerque with her woodworking, recorder-playing, singing husband (who is also a mercenary engineer) and her three practically-grown unschooled offspring. Kirby is 20 and has a new Wii (Nintendo thing), so he can take breaks from World of Warcraft (when he's not at work). Marty is 17, reads comic books, and just became a squire to a king (medieval parallel life and all, when he's not at work or running around with friends). Holly is 15 and is driving when the traffic's not too heavy.

Bob Collier's son learned to drive differently—read that here